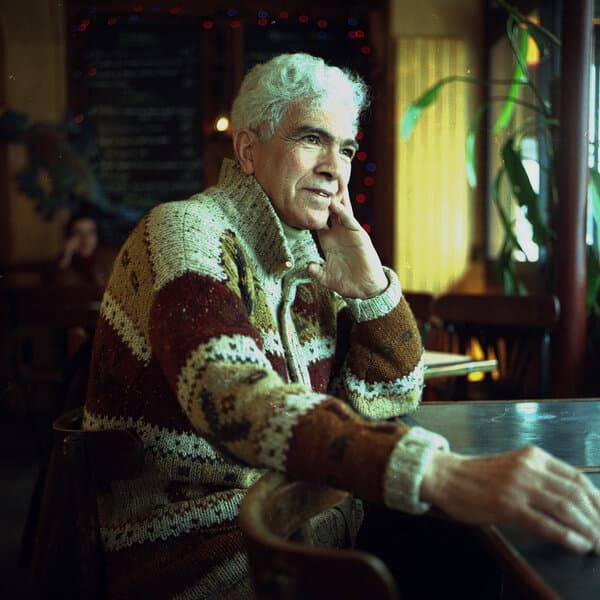

Mohammed Harbi, Historian Who Reshaped Algerian Narrative, Dies at 92

Mohammed Harbi, a prominent Algerian historian and intellectual whose rigorous scholarship fundamentally challenged and reshaped the official narrative of Algeria's war of independence, has died at the age of 92. Harbi passed away in Paris, according to family members and colleagues who confirmed his death on Friday. Born in 1933 in the town of Jijel, Harbi came of age during a period of intense colonial repression and rising nationalist fervor. He joined the National Liberation Front (FLN) at a young age, becoming deeply involved in the political struggle against French rule. During the war, he served as a key aide to Ahmed Ben Bella, one of the revolutionary leaders who would eventually become Algeria's first president. However, Harbi's relationship with the post-independence government quickly soured. He witnessed firsthand the internal purges, the consolidation of power, and the betrayal of revolutionary ideals that marked the early years of the Algerian state. By 1965, following Ben Bella's ouster by Houari Boumediene, Harbi had fled the country, eventually settling in France where he would spend the remainder of his life in exile. It was in this forced exile that Harbi transformed from a political actor into a formidable historian. He pursued academic studies, eventually earning his doctorate and establishing himself as a leading scholar at the University of Paris 8. His work was characterized by a relentless pursuit of truth and a refusal to accept mythology in place of facts. His seminal work, 'The FLN: A History,' published in 1976, remains perhaps the most comprehensive and critical account of the nationalist movement ever written. Drawing on his own experiences and extensive archival research, Harbi exposed the internal fractures, ideological debates, and power struggles that existed within the FLN from its earliest days. This work was banned in Algeria for decades, a testament to the threat his objective analysis posed to the ruling regime. Harbi's scholarship was not limited to the independence war. He produced extensive works on the evolution of the Algerian state, the nature of military involvement in politics, and the complex relationship between Islam, socialism, and nationalism in the Algerian context. He argued passionately that understanding the full complexity of the revolution was essential for building a democratic future. For decades, his work remained largely inaccessible within Algeria itself, though pirated copies circulated among students and intellectuals. He was often dismissed by official state media as a 'renegade' or 'pseudoscientist,' labels he wore as badges of honor that validated his independence from state propaganda. With the political liberalization of the 1990s and particularly following the death of President Boumediene, Harbi's work began to gain a wider audience in Algeria. A younger generation of historians and political scientists, eager to understand their country's past beyond official hagiography, discovered his rigorous analysis. His books became foundational texts for serious study of Algerian history. Colleagues describe Harbi as a man of immense integrity and courage, who never compromised his intellectual principles despite the personal cost of permanent exile. He maintained close ties with the Algerian diaspora and continued to write and comment on Algerian politics until his health prevented him from doing so. His passing marks the end of an era for a generation of intellectuals who sought to democratize historical knowledge and hold power accountable to truth.